Roger Clarke's Web-Site

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024

Infrastructure

& Privacy

Matilda

Roger Clarke's Web-Site© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024 |

|

|||||

| HOME | eBusiness |

Information Infrastructure |

Dataveillance & Privacy |

Identity Matters | Other Topics | |

| What's New |

Waltzing Matilda | Advanced Site-Search | ||||

Preliminary Working Paper of 8 August 2023

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 2023

Available under an AEShareNet ![]() licence or a Creative

Commons

licence or a Creative

Commons  licence.

licence.

This document is at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/ATS.html

This paper draws on a generic theory of authentication to consider the authentication of a key sub-set of expressions in text: those that constitute statements whose reliability is important to economic and social processes. The terms used for such statements is 'textual assertions'. Consideration is given to the responses to recent waves of misinformation and disinformation, including the 'fake news' pandemic. It is contended that the authentication of textual assertions lies within the domains of the IS discipline and IS practice, and suggestions are made as to how contributions can be made by IS academics and practitioners.

The main focus of both practice and research in Information Systems (IS), throughout their first 60 years, has been on structured data. By this is meant collections of records, each relating to a particular thing, comprising multiple data-items each of which has a more-or-less tightly-defined meaning, for which content may be mandatory or optional, and many of which are subject to data-item-value specifications, such as numeric or currency content, or a defined set of permitted values. IS traditionally involve the validation, editing, processing and analysis of the content of such data-items and records, enabling the delivery of value to system users and system sponsors, and in some cases to other parties.

As technology has advanced, additional forms of data have become increasingly important. Image, audio and video are now mainstream, and have been within the field of view of IS practitioners and IS researchers for nearly half the life of the profession and discipline. This paper is concerned with a further form of data that for some decades has been given only limited attention: data held in textual form, representing words expressed in natural languages, but in visual form.

For many language groups, including in most of the 'western' world, the term 'text' refers to expressions of natural language in characters, symbols or glyphs that make up alphabets. In an alphabet, each character represents one or more sounds. The origins of many alphabets are usually traced from Sinai c.1700BC, via the Pheoenicians c.1000-500BC, and, in the case of contemporary Western European languages, onwards via Ancient Greek and Latin. Western European alphabets have 21-33 characters, in some cases with qualifying glyphs called 'diacritics', such as umlauts and cedillas. Alphabets provide great flexibility and in many cases are used to express multiple languages. Outside Western Europe, the sizes of alphabets vary widely, the largest (Khmer) having 74 characters.

In alphabets, each glyph represents either one short sound, or multiple, alternative short sounds (such as 'c' as in 'cat' and 'c' as in 'mice'). Two categories of sounds are distinguished. Consonants involve some part of the mouth being closed, whereas the air-path is more open in the case of vowels. The alphabet used in English, a modern successor to the Latin or Roman alphabet, has 26 letters that are used to represent 24 short consonantal and 20 short vowel sounds. Some alphabets, however, called abjads and abugidas, focus on consonants and represent at most a sub-set of the vowel-sounds that its speakers use.

A different approach is taken by syllabaries. Each glyph represents a more extended sound referred to as a syllable, in most cases comprising a combination of consonants and vowels. Examples include hiragana and katakana (two ways of expressing Japanese), each with 46 characters. Cherokee has 85 characters, and the ancient language Mycenaean Greek, Linear B, has 87. Some syllabaries have even larger numbers of characters.

A further important means of expression of natural language is logograms, which originated earlier than alphabets and syllabaries. In logograms, many glyphs began as pictures but each came to represent a word, or a word-part called a morpheme. Examples include 'Chinese characters' (often referred to in English using the spoken-Mandarin expression Zhongwen), Japanese Kanji, Korean Hanja, several ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic scripts, and many other scripts used in ancient Asia and in Mayan and Aztec cultures. The number of characters in logographic scripts is generally large, and the set is extensible, indicatively about 1,000 for Sumerian cuneiform, 8,000 for Kanji, and 50,000 for Zhongwen and Hanja.

The term 'text' is used here to encompass all visually-recorded natural language, using any alphabet, abjad, abugida, syllabary or logographic script (Ramoo 2021). This approach is consistent with the Unicode standard, which accomodates character-sets intended to encompass all written natural languages. Unicode currently supports character encodings into machine-readable form of c.150,000 characters (Unicode 2022).

Text can be used in disciplined ways, which can be readily applied to structured data. For example, a data-item called Colour could be defined to permit a set of data-item-values that comprise, say 'red', 'green' and 'blue' (and/or 'rouge', 'vert' and 'bleu', etc.) - encoded for machine-readability according to the Unicode specification. However, the original purpose of natural languages, and the ongoing practice, is not constrained in this way. In many languages, text has considerable diversity of grammar and spelling, and a great deal of semantic richness and hence ambiguity. It is also open to 'word-plays', such as pun (intentional ambiguity), metaphor and simile, and to irony (an intentionally false statement intended to be apparently so). The meaning of any given passage of text also depends on the surrounding text and multiple other elements of the context in which it was uttered. Semiotics, the study of the use of symbolic communication, encompasses three segments (Morris, 1938):

The structured data that IS has historically been concerned with is designed for efficiency, and this results in a focus on syntactic aspects, and on intentionally formalised and constrained semantics. The vast majority of text, on the other hand, evidences richness, flexibility of use, and context-dependence. Syntactics, including grammar and punctuation, provide some degree of structural framing, but considerable effort is required to interpret the content's semantics and pragmatics, and ambiguity is inherent.

A further complexity arises, in that a differentiation needs to be drawn between formal text, on the one hand, and spoken words that are transcribed into text, on the other. Most written languages have more-or-less fixed rules of grammar, which generally require the use of sentences, define what patterns do and do not constitute sentences, and require variants of some word-types in particular contexts. Although some uses of spoken language respect the rules of written grammar, most do not. As a result, transcribed text requires more interpolation and interpretation by the reader, and embodies an even higher degree of ambiguity than formal text.

Text is used as a primary basis for communication among humans. In a rationalistic approach to text, "it is assumed that each sentence in a natural language ... can be set into correspondence with one or more possible interpretations in a formal language ... for which the rules of reasoning are well-defined" (Winograd & Flores 1986, p.18). Those authors argue that, although this approach may be applicable in some circumstances, it fails in a great many others. Mention has already been made of ambiguities, diversity of grammar and spelling, playfulness in the use of natural language, and contextual dependence.

Beyond those issues, the propositions of hermeneutics are that the intention of the utterer is not directly conveyed to the reader, but rather that text is interpreted by the reader; and that the interpretation is based on that person's 'pre-understanding', such as their educational and cultural background and worldview (Gadamer 1976). In one of the clearer sentences in translations of Heidegger, "The foundation of any interpretation is an act of understanding, which is always accompanied by a state-of-mind ..." (Heidegger 1962, p.253). In their discussion of computers and cognition, Winograd & Flores (1986 pp.111-114) instead adopt the term 'background' for the basis on which a human, or a computer, builds their/its interpretations. Because of the diversity among readers, any given passage is likely to be subject to multiple interpretations depending not only on the richness and ambiguities mentioned earlier, but also on the 'set' or 'mindset' of each human reader and/or the memory-states of each artefact that ingests it.

All text is subject to interpretation in ways other than that intended by its author. One example is the reading-in of sub-texts. Another is critique from the viewpoint of alternative value-sets, such as feminist readings of works written in male-dominated contexts, and post-colonialist perspectives on works originating in imperialist contexts. A further strong form of critical interpretation is 'deconstruction' in the sense of Derrida (1967), that is to say, the exploration of tensions and contradictions among the nominal and real intentions, and the various interpretations, of passages of text.

Human endeavour, economic and social alike, needs to overcome all of these challenges. Individuals need to understand other individuals' explanations, instructions, and advice on how to perform tasks and achieve outcomes. Mutual understanding between and among people is needed, to enable negotiations in familial and social contexts, about the price of goods and the terms of trade, about the elements of a Bill tabled in a parliament, and about the terms of an armistice. Then, beyond understanding, people need to be able to place reliance on statements made in text, and in transcriptions of statements made orally or recorded in audio form.

Given the complexities discussed in the preceding paragraphs, it is unsurprising that IS research and practice, with their focus on efficiency and syntax, have not been very active in their support for textual statements. I contend, however, that IS practice and IS research now need to invest far more effort into the management of text. One reason is that IS have matured far beyond structured data, and process text as a matter of course. Another is that system users and system sponsors demand that IS deliver value across all forms that data takes. A further motivator is that individuals who work in IS will find their employment opportunities rapidly decreasing unless their capabilities measure up to their employers' expectations.

This paper's general purpose is to make a contribution to IS practice and practice-relevant IS research in relation to the handling of text, with a particular focus on the reliability of statements. In conducting the analysis, some assumptions are made. In particular, the metatheoretic assumption is adopted that, in the circumstances in which IS practice and practice-relevant IS research are conducted, there is no expressible, singular, uncontestable 'truth', or at least none that is accessible within the context of IS practice. A corollary of that assumption is that it is untenable to assume that the reliability of statements can be determined by reference to a singular, accessible truth, and hence terms such as 'verification' and 'validation' are inapplicable, and a more qualified term is appropriate, such as 'authentication'. It is acknowledged that this assumption limits the relevance of the present analysis in some circumstances. In particular, it may not be applicable to IS research that adopts the more extreme forms of positivism, nor to IS practice in relation to highly-automated decision-and-action systems such as industrial control and autonomous guidance systems. This paper's specific purposes are to apply a generic theory of authentication to textual statements relevant to IS, taking into account the complexities outlined above, with the aims of providing guidance to IS practice, and offering a framework within which practice-relevant IS research can be conducted.

The paper commences by identifying those categories of textual statements whose reliability requires evaluation, referred to as 'textual assertions'. These include statements relevant to the processes of commerce and government, such as those made by sellers, applicants for loans and insurance, job applicants, income-earners submitting taxation returns, and welfare recipients. The scope extends further, however. IS now involve the reticulation of news and the expression of opinion, in both formal and social media. This makes it necessary to encompass the phenomena of misinformation and disinformation. A generic theory of authentication is then outlined, and applied to the authentication of textual assertions.

One aspect of the richness of natural languages is that they support many kinds of utterances. This section draws on linguistic theories to distinguish categories of utterance whose reliability may need to be evaluated [REFS from descriptive linguistics]. The relevant kinds of utterances are referred to here using the collective term 'assertions' - noting however that this use of the term 'assertion' differs from the term 'assertive' as it is used in linguistics. Consideration is given to the forms that utterances take, and the kinds of expressions are identified that do and do not constitute assertions that need to be relied upon. The grammars of languages, and especially verb-structures, vary enormously. The examples in this paper are limited to the English language, and hence require further consideration even for languages with similar moods and tenses, such as German, let alone for languages whose linguistic profiles are radically different from English.

The following working definition is adopted:

An Assertion means a statement on which some entity is likely to place reliance, and hence to perceive value in ensuring that there are adequate grounds for treating the content of the utterance as being reliable

For that to be the case, it is necessary for the utterer to have a commitment to the utterance's reliability. A commitment may be simply moral; but relying parties will tend to have greater confidence in the utterance's reliability if there are consequences for the utterer should the utterance transpire to have not been trustworthy.

A discussion of what the authors call 'conversation for action' appears in Winograd & Flores (1986 pp.64-68). It uses a state transition model to depict what, in contract negotiation terms, are invitations to treat, offers and acceptances, culminating in an agreement, but with the scope for non-completion through rejection, withdrawal and renege. An offer, an acceptance and an agreement are important examples of utterances whose reliability parties need to authenticate. Another relevant source of insight is Speech Act Theory. This identifies categories of utterances that are described as 'performative', in that they constitute acts, or 'illocutionary', in that they motivate action Searle (1975).

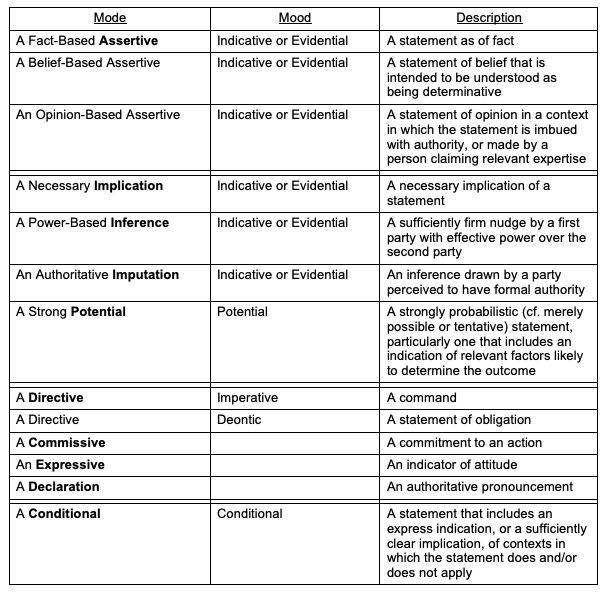

Two linguistic constructs of direct relevance to this paper are 'mood' and 'modality', which together reflect the ontological character of the subject, such as its reality or unreality, and the degree of certainty. An accessible depiction of modality is that it "covers the semantic space between `yes' and `no'" (Yu & Wu 2016). Statements are highly likely to be relied upon when they are black or white, but decreasingly likely as their strength fades from either end of that spectrum to shades of grey. Applying these bodies of theory enables a variety of relevant categories to be distinguished. These are introduced in the following text, and summarised in Table 1.

The primary form of Assertion of relevance to this topic is an intentional communication, referred to in Speech Act Theory as an Assertive, which is expressed in the Indicative or Evidential mood. This has several variants. The first is commonly referred to as a assertion of fact, of a fact-based assertive. To allow for statements expressed confidently but actually erroneous, a more descriptive term is a statement 'as of fact'. A simple example is that 'all swans are either white or black' is conventionally regarded as factual. The statement 'all swans are white' was for centuries factual, at least within a geographical context, but was subsequently disproven by the European 'discovery' of Australian swans. However, the short statement is encompassed by the expression 'statement as of fact'. A richer example is an affirmation of accuracy and completeness of the data provided in an application for an insurance policy (which is commercially important because, if any of the data is later shown to be materially incorrect, the insurer can void the policy).

Two secondary forms of assertive may also need to be evaluated for their reliability and significance. Whereas, in general, an assertion of belief falls outside the domain of interest, some such assertions are significant because they are intended to be understood as being determinative. Forms that are likely to affect and even drive action include 'It's a given that', 'It's axiomatic that', 'It's an article of faith that', and even 'I believe that', where the utterer has high standing or political power.

Similarly, although most statements of opinion are unlikely to constitute assertives, the scene changes in a context in which the statement is imbued with authority, or made by a person claiming relevant expertise. Examples of opinion-based assertives include a considered opinion uttered by a person in a senior position in a religious organisation or a cult, a considered expression of opinion in a report by a consultant hired for the express purpose, and evidence by an expert witness before a court of law.

Most assertions embody explicit declaration of a claimed fact. However, there are circumstances in which implied claims may fall within the category 'assertive'. One example is a necessary implication of any kind of statement, e.g. 'A regrets drinking before driving' implies 'A drank before driving'. Beyond implication, an assertive may also arise by inference or imputation. Where a power relationship exists between the utterer and another party, it is more likely that the second party will infer that a statement expressed in a neutral tone of voice is a firm nudge that needs to be acted upon. The word 'impute' is often used as a strong form of 'infer', as occurs when the inference is drawn by a third party with perceived authority, such as a court imputing an intention on the part of the accused, or a social welfare agency imputing interest earned on an asset.

A further relevant category is statements in Potential mood, whereby an utterance is qualified in a sufficiently specific manner. Potentials are assertions where they are strongly probabilistic rather than merely possible or tentative, and they indicate relevant factors likely to determine the outcome. Indicators of an assertive include 'The time is bound to come when <statement>' and 'As and when <future condition> comes about, <statement>'.

In addition to mood, two further grammatical features may be relevant: tense and aspect. Combining them into familiar patterns, distinctions are usefully made among the following kinds of expressions, all of which signal a statement whose reliability is likely to require evaluation:

Other kinds of performative utterance identified in Speech Act Theory are also categories of statement whose reliability may require evaluation. A Directive, such as a command, request or advice may be expressed in Imperative mood, e.g. 'Fire [that weapon]!', or may be expressed as a notice of dismissal from employment, approval of sick leave, or suspension of driver's licence. Alternatively, a Directive may be in Deontic mood, as a statement that an obligation exists, e.g. 'You are required to comply with [section of Act]', and statements using the modal verbs 'must', 'shall', 'have to' or 'has to'.

A Commissive is a commitment to a future action, generally expressed as a promise or an undertaking, e.g. to make monthly repayments, to satisfy specified KPIs, or to transfer a real estate title. An Expressive conveys an attitude, such as congratulations, excuses or thanks, such as an entry in a membership register as an honorary life member, a notification of incapacity to fulfil a commitment because of accident or illness, or communication of an honour conferring a postnominal such as VC, KC, CPA, FIEEE. A further category identified in Speech Act Theory is a Declaration, an authoritative pronouncement such as marriage, baptism or guilt. It therefore encompasses an entry in a register of shareholders, of licensed drivers, of persons convicted of a criminal offence, or of users authorised to access a particular IS or particular categories of data.

Finally, Conditional mood involves a qualification to an utterance by declaring its reliability to be dependent upon some specified factor. This includes those uses of the modal verb 'can' that convey the possibility but not necessity of doing something. Such utterances are assertions if they communicate the scope of the contexts in which the statement does or does not apply. This may be express, using such expressions as 'provided that <condition>', 'where <condition> applies', 'but if', or 'unless'. It may, however, be implied or reasonably inferred from the statement and its context.

It is important not only to define what categories of utterance represent assertions that may be in need of authentication, but also to identify categories of statements that are out-of-scope for the purpose of this analysis. Table 2 presents the primary non-relevant categories. In many cases, however, boundary-cases and grey-zones exist. For example, an Interrogative may have authority and have motivational force where 'Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?' is uttered by a king, or 'Does any true believer really think that this apostate should remain alive?' by a senior cleric.

This section has utilised mainstream concepts in descriptive linguistics to identify the expressions that indicate Assertions whose reliability may need to be evaluated. The following section considers a foundational question underlying the authentication of assertions: how can an evaluator distinguish between reliable and unreliable Assertions?

Unreliability of statements has challenged society for millennia. Courts of law have developed arcane rules of evidence in order to deal with information whose qualities may or may be such as to provide a basis for reaching a judgment. Meanwhile, natural philosophy, and the individual sciences that grew out of it, have forged their own cultures, with principles, norms and procedures intended to enabled deprecation of less reliable assertions, and cautious adoption of more statements that reach a threshold of reliability. This section considers the characteristics associated with the unreliability of assertions.

The extent to which unreliability exists is attested to by the richness of the language with which variants of unreliable statements are described. The term 'propaganda' is commonly used to refer to information of a misleading nature used for political purposes, including 'half-truths' and other forms of communication of selective or partial information or biased expression, mis-descriptions, rumours, misrepresentations and Orwellian 'newspeak'. Public relations (PR) is nominally concerned with controlled dissemination of information in order to influence perceptions. Advertising has the more specific purpose of encouraging sales of particular goods or services, or encouraging a positive disposition to particular goods or services. To many people, however, the practices of both PR and advertising are barely distinguishable from propaganda. In addition to active dissemination of wrong, false, unfounded and misleading statements, readers are also routinely misled through negative forms of misleading behaviour, including cover-stories, cover-ups, secrecy, and measures to suppress information such as the oppression of whistle-blowers.

The term 'fake news' emerged a century ago, to indicate unreliable information published in a form and/or venue consistent with the idea that it was factual reporting of news. It was associated with what were referred to through the twentieth century as 'yellow journalism' in the US and 'the tabloid press' elsewhere in the English-speaking world. The business model was, and remains, founded in entertainment rather than in journalism. With the emergence of social media from about 2005, and 'tech platforms' since about 2015, the opportunity to publish fake news has extended far beyond the media industry, such that the phenomenon is now overwhelming traditional news channels.

Categories of 'fake news' have been identified (Wardle 2017) as:

During the second decade of the new century, US personality Donald Trump extended the use of propaganda in election campaigning and in government by adopting the forms and channels of fake news. This further-debased form of political behaviour gave rise to the term 'post-truth', to refer to "circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief" (OL 2016).

The terms misinformation an disinformation have been much-discussed since 2015. However, the definitions associated with them commonly use the unhelpful term 'false'. Such uses embody the impractical criterion of statement veracity, whereas tests can be much more readily devised for recognising various forms of statement unreliability. Ongoing discussions in philosophy sustain the fiction that true/false tests are a useful approach to authenticating assertions of fact. For example, much of Floridi's work is committed to 'veridicality' (e.g. Floridi 2007, Soe 2019) and the alethic modalities of truth, such as necessity, possibility and impossibility (Floridi 2011). Some of the Codes of Practice issued by governments attempt to mitigate the harmful effects of 'false' by including the term 'misleading' as an alternative, but they lack definitional clarity (e.g. DIGI 2021 p.6 at 3.6, (EU 2022, p.1).

The approach adopted here avoids the unhelpful complexity and resultant confusion in current official documents by treating the common feature between the two terms as 'unreliability' not 'falsity', but, in common with them, differentiates the two categories on the basis of whether there is an evident 'intention to mislead':

Disinformation means one or more unreliable Assertions that were demonstrably intended by the utterer to mislead the reader or hearer

Misinformation means one or more unreliable Assertions that were not demonstrably intended by the utterer to mislead the reader or hearer

In effect, Disinformation is an error of commission, culpable at least in a moral sense. Misinformation, on the other hand, involves a moral judgement of 'not guilty' of intent (or at least 'not proven', in the sense in which that finding has been used for two centuries in Scottish law). Moral responsibility for Misinformation is accordingly at a lower level than that for Disinformation, for example at the level of negligence, recklessness or carelessness.

The degree of apparent authenticity or convincingness of Dis-/Mis-information varies greatly. Language can be used in such a manner as to have one meaning or shade for most people, but a different meaning or shade for initiates, 'people in the know', or 'the target audience'. Variants of expression can sustain a substantial kernel of reliability but deflect the reader toward an interpretation that, to most readers, lacks legitimacy. The use of sophisticated tools, such as 'air-brushing' for wet-chemical photography, 'photoshopping' for digital images, and 'generative AI' for text, have given rise to the notion of 'deepfakes' (Sample 2020). A further consideration in the discussion of Disinformation and Misinformation is the shades of meaning that arise in different areas of use, such as health advice, political debate, strongly contested public policy areas such as race relations, immigration and abortion, the credibility of public figures in government and business, and the credibility of entertainers, sportspeople and 'celebrities'.

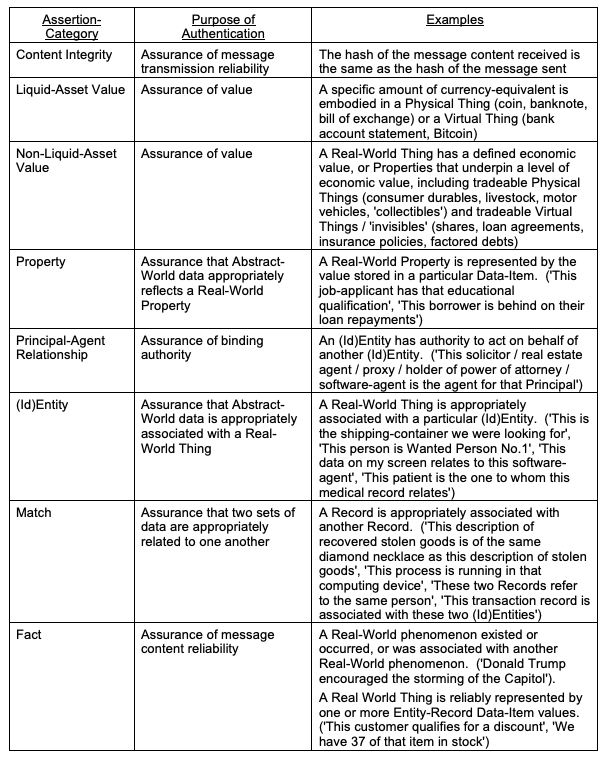

The analysis to date has considered the nature of textual statements, and identified forms of expression that constitute Assertions, in that they are relied on, and hence their reliability may need to be checked. It has also considered the notion of unreliability, with a focus on the concepts of disinformation and misinformation. The following section identifies a range of assertion-categories that are of importance in various forms of IS, because they have economic and in some cases also social significance.

In prior work, a categorisation of assertion-types has been proposed. The emphasis in those papers is on the exchange of goods and services. The work is predicated on a set of assumptions declared in a Pragmatic Metatheoretic Model (PMM) intended to reflect the conventions adopted by IS practitioners, and documented in (Clarke 2021). The key postulates underlying the PMM are as follows:

Building on those assumptions, two further papers, Clarke (2023a, 2023b), identify categories of assertions that are important in commerce, and that therefore are commonly supported by IS and understood by IS practitioners. Those categories are summarised in Table 3. The first category involves syntactics, being Assertions that a message has retained its integrity during its transmission from sender to recipient. Most, however, have substantial semantic significance. Effective commerce depends on many Assertions relating to the value of physical and virtual goods and services. In relation to liquid assets, that is to say currency and its equivalents, a range of assurances and undertakings can be provided. Other kinds of assets require particular kinds of assertions, reflecting different forms of intrinsic and extrinsic value, and the physical or virtual nature of the asset.

The first seven, specific categories in Table 3 are examined at length in Clarke (2023a, 2023b), and are not further discussed in the present paper. The eighth and last of the categories is the previously-discussed notion of an Assertion as of Fact. In the referenced works, this is only briefly considered, and in the context of structured data rather than the textual form that is the subject of the present paper. The 'Assertions of Fact' category is a generic or meta-concept, with some or all of the other categories as specific instantiations of it. Evaluation of the reliability of each assertion-category requires a customised Authentication process, and particular Evidence. The following section outlines a generic theory of Authentication, and the final section of this paper applies that generic theory to the 'Assertions of Fact' category.

Earlier sections have defined categories of utterances, referred to as Assertions, whose reliability may need to be evaluated, and considered the sources and nature of unreliability. This section discusses the nature of evaluations of statement reliability, drawing on Clarke (2023b) and its sources. The term 'authentication' (and its deprecated alternatives 'verification' and 'validation') are commonly used to refer specifically to evaluations of identity assertions, especially in online contexts, usually by means of the production of an identifier and a shared secret. This paper adopts the position that the need to evaluate reliability arises in relation to many forms of Assertion, and that authentication is the appropriate term to apply to the activity.

A fundamental assumption of this work is that it is untenable to assume that each, or any, assertion can be resolved by reference to a singular, accessible truth. Rather than testing whether a statement "is true", the following, practical operational definition is adopted:

Authentication is a process that establishes a degree of confidence in the reliability of an Assertion.

Some Assertions refer to the Real World, such as 'There are no relevant Things (stock-items) in the Thing that is allocated to that particular category of stock-items (a storage-bin)'. Other Assertions relate only to the Abstract World, such as 'A Transaction-Record gives rise to changes in (Id)Entity-Records', or 'The value of this Data-Item in this Record matches to this other Data-Item in another Record'. Abstract-World Assertions, and inferences from them, are of value to decision-making. On the other hand, the Authentication of Assertions that relate solely to the Abstract World can provide only limited assistance in assuring reliability, because all such propositions implicitly assume that the Assertions and inferences are representative of the Real World. Of much greater value is the Authentication of Assertions that cross the boundary between the Real and Abstract Worlds, such as 'The physical stock-count of Things in a particular storage-bin did not get the same result as the value stored in the Stock-Count Data-Item in the relevant Record'.

Authentication processes depend on two activities:

Consistently with OED definition III, 6: "... facts or observations adduced in support of a conclusion or statement ...", but avoiding aspects that presume accessible truth, the following working definition is adopted:

Evidence, in relation to the Authentication of an Assertion, is data that tends to support or deny that Assertion.

An individual item of Evidence is usefully referred to as an Authenticator. A common form of Authenticator is content within a Document. In this context, the term Document encompasses all forms of 'hard-copy' and 'soft-copy', and all formats, often text but possibly structured data, tables, diagrams, images, audio or video. Content on paper, or its electronic equivalent, continues to be a primary form. It is noteworthy, however, that, in legal proceedings, distinctions are drawn among testimony (verbal evidence), documentary evidence, and physical evidence.

Where the subject of the Assertion is a passive natural object, an animal or an inert artefact, the Authentication process is limited to checking the elements of the Assertion against Evidence that is already held, or is acquired from, or accessed at, some other source that is considered to be both adequately reliable and sufficiently independent of any party that stands to gain from masquerade or misinformation. Some Authenticators carry the imprimatur of an authority, such as a registrar or notary. Such an Authenticator is usefully referred to as a Credential (cf. "any document used as a proof of identity or qualifications", OED B2). Humans, organisations (through their human agents) and artefacts capable of action, can all be active participants in Authentication processes. A common technique is the use of 'challenge-response' sequence, which involves a request to the relevant party for an Authenticator, and a communication or action in response.

In a legal context, the term probative means "having the quality or function of proving or demonstrating; affording proof or evidence; demonstrative, evidential" or "to make an assertion likelier ... to be correct" (OED 2a). In the law of evidence, "'probative value' is defined to mean the extent to which the evidence could rationally affect the assessment of the probability of the existence of a fact in issue" (ALRC 2010, 12.21). After evidence has been led, cross-examination may be undertaken by the other party, with the intention of clarifying the meaning of, or undermining the impact of, the original spoken testimony or written evidence. It is also open to either party to present counter-evidence, as a rejoinder to evidence submitted by the other.

A further aspect of the use of evidence in legal contexts is that a court is required to treat some kinds of assertion as rebuttable presumptions, to be treated as being reliable unless and until case-specific evidence is presented that demonstrates otherwise. This makes clear on which party the onus of proof lies. In civil jurisdictions, the standard of proof is 'preponderance of the evidence' or 'preponderance of the probabilities', whereas in criminal jurisdictions the threshold of proof is generally 'beyond a reasonable doubt'.

The law also recognises that economic constraints apply to evidence-collection and authentication processes: "a decision is better if it is less likely to be erroneous, in light of the actual (but unknown) outcome of the decision that would be known if there were perfect information. The quality of the decision takes into account the magnitude of ... harm from making the erroneous decision [and] the probability of doing so. Decision theory similarly can be used to rationally decide how much information to gather. It does so by balancing the costs and benefits of additional imperfect information in terms of making better decisions" (Salop 2017, pp.12-13).

In the courts, the authentication of assertions plays a significant role in the court's utterance of a binding determination. In the context of investigations by a law enforcement agency, on the other hand, authentication plays a rather different role. An investigator seeks patterns or relationships in data, which at best will point firmly towards the resolution of a case, but which will desirably at least close off an unproductive line of enquiry or lead the investigator towards more promising lines. Linked with this looser form of evidentiary standard is the concept of confirmation bias, which describes the tendency to take notice of evidence that supports a hypothesis rather than that which conflicts with it, and the even more problematic tendency to actively look for evidence that will support rather than refute a currently favoured proposition (Nickerson 1998).

Confirmation bias is just one of a range of risk factors that impinge on the quality of Authentication processes. An appropriate balance needs to be achieved between the harm arising from false positives, which are Assertions that are wrongly accepted; and false negatives, which are Assertions that are wrongly rejected. Accidental mistakes are one source of quality issues. Quality is a substantially greater challenge, however, where parties are motivated to contrive false positives or false negatives. Actions can be taken by a party in order to generate false positives that serve the interests of that party, e.g. masquerade or 'spoofing', to provide spurious support for a claim. Similarly, false negatives can be contrived, through avoidance, undermining or subversion of the process.

To deal with the challenges that quality faces, safeguards are needed to limit the extent to which parties may succeed in having Assertions wrongly accepted or wrongly rejected, in order to gain advantages for themselves or others. The level of assurance of an Authentication mechanism depends on the effectieveness of the safeguards against abuse, and hence on whether an Assertion can be effectively repudiated by the relevant actor. It is conventional to distinguish multiple quality-levels of Authentication, such as unauthenticated, weakly authenticated, moderately authenticated and strongly authenticated. Organisations generally adopt risk management approaches, which accept lower levels of assurance in return for processes that are less expensive, more practical, easier to implement and use, and less intrusive (Altinkemer & Wang 2011).

Where quality shortfalls occur, additional considerations come into play, including the following:

This section applies the generic theory of Authentication outlined above to the particular category of Assertions that have been the focal point of the paper. It defines and articulates the notions of textual assertion and textual assertions as to fact, then examines ways in which evidence may be gathered and applied in order to authenticate these important forms of Assertion.

As implied through the course of this paper, the focus is on the following notion:

Textual Assertion means a visual representation of an Assertion expressed in, in principle, any natural language that has a visual form

The primary focus is on instrumentalist text whose intended meaning is reasonably clear or extractable, as distinct from, for example, poetry and poetic prose, which are intentionally evocative and ambiguous. Polemic, hyperbole and satire are intentionally included within-scope, however, because they are pragmatic, in the sense in which that term is used in semiotics. Text remains within-scope where is formatted, e.g. using bullets, numbered sub-segments and tables. Many other forms of statement are not directly addressed here, however. They include the following, referred to below using the collective term 'graphics':

Uses of text fall out-of-scope of the present analysis where the text is secondary because graphic elements play a significant semantic role. Common hybrid forms that relegate text to a secondary role in communication include created images (diagrams, cartoons, infographics), icons, captured images (captioned or annotated photographs) and synthesised images (captioned or annotated CGI). Hybrids may be appropriate to include within scope, however, where the utterer's use of graphical forms is supportive of the text, and the utterer's intentions in relation to the interpretation of the graphics are clearly elucidated. Graphics embody far greater richness of alternative interpretations, so the effective Authentication of hybrid forms needs to apply complementary techniques to the textual analysis tools considered in this section.

In Table 3, multiple assertion-categories were described. The focus here is on the last, generic category. The other, specific categories are the subject of specific treatment in Clarke (2023a, 2023b). An Assertion in the category 'Fact' may indicate something about a Thing or Event in the Real World (e.g. 'Person-A performed Action-B'). Alternatively, it may associate with a Property of a Real-World Thing or Event an Abstract-World Data-Item in a particular Record (e.g. 'Our records show that, across our four distributed warehouses, we have a dozen instances of Product-C available for delivery to customers', 'This very collectible vehicle was driven by Michael Schumacher in three Grand Prix races'). To authenticate an Assertion in this category, assurance is needed of the reliability of its content.

Such an Assertion may or may not be supported by Evidence or be a reasonable inference from Evidence. It may or may not be the subject of counter-evidence. (If the 'veridical' assumption were to be adopted, it could be either 'true' or 'false'). It merely indicates that the utterer claims that it is so. Hence, the term needs to be interpreted to apply to a statement of the nature of 'All swans are white', despite the existence of Evidence that denies that statement's reliability. The term used, and its definition, need to reflect these features in order to avoid misunderstandings. The following working definition is adopted:

Assertion as to Fact means a Textual Assertion that involves at least one Real-World phenomenon

This section considers means whereby evaluation of the reliability of Assertions as to Fact may be undertaken, and what kinds of Evidence can support those processes. Some such Assertions involve structured data, and hence the well-established criteria for data and information quality can be applied (Clarke 2016, p.79). These are applicable even to fuzzy statements about, for example, the number of people at a meeting (e.g. <a range of numbers>, at least <some number>, no more than <some number>, few/some/many). Those expressions may be able to be compared with one or more reliable sources of information about the meeting, and the reasonableness evaluated relative to the context. Similar techniques can be applied to statements about the date and/or time of an event, the sequence in which two or more events occurred, or the identities of individuals or organisations involved in them.

For Assertions that do not involve structured data, a range of approaches have been adopted to Authentication. Reference was made earlier to the nature of evidence and its authentication within court systems, and in criminal investigation activities of law enforcement agencies. Another approach depends on the application of 'critical thinking', by which is meant "the ability to analyse and evaluate arguments according to their soundness and credibility, respond to arguments and reach conclusions through deduction from given information" (Tiruneh et al. 2014). However, publications on the topic generally propose ad hoc principles, and few attempt a process approach.

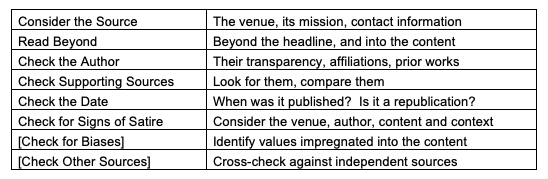

The spate of 'fake news' issues during the Trumpian 'post-truth' era since about 2010 has given rise to a literature on how to recognise untrustworthy Textual Assertions. Sukhodolov & Bychkova (2017) suggest that the objectives pursued by fake-news creators and publishers can be classified into political advantage, financial fraud, reputational harm, market manipulation, site-traffic generation, entertainment, or opinion formation or reinforcement. A widely-cited list of relevant criteria for determining whether an Assertion is 'fake news' is provided by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA), and is summarised in Table 4.

Adapted from IFLA (2017)

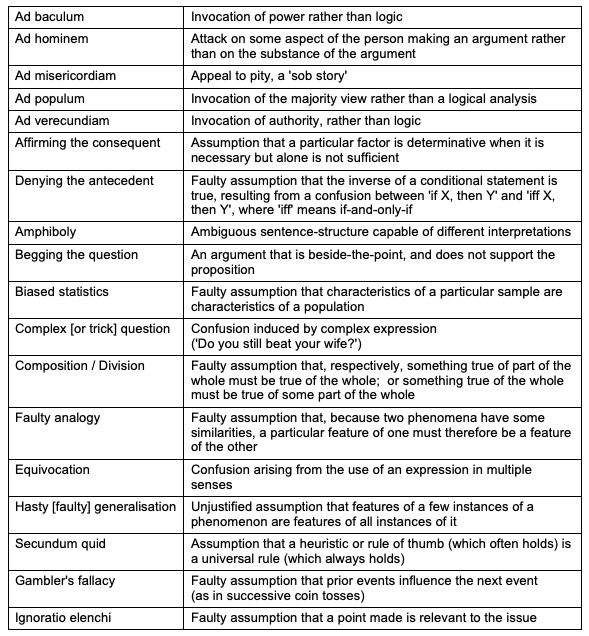

The authors of Musi & Reed (2022) drew on in particular Hamblin (1970) and Tindale (2007), and cited the common core dubbed by Woods et al. (2004) as the 'gang of eighteen' fallacies. See Table 5. It is noteworthy, however, that the Wikipedia entry for 'List of Fallacies' distinguishes not 18, but about 140, forms of fallacious reasoning that occur in Misinformation, and that can be harnessed by authors of Disinformation.

As listed by Woods et al. (2004), pp.4-5

On the basis of Fallacy Theory, Musi & Reed (2022) claim to "identify [4 groups of] 10 fallacious strategies which flag misinformation and ... provide a deterministic analysis method by which to recognize them" (p.349). These are Evading the burden of proof, The (un)intentional diversion of the attention from the issue at hand (including Straw-man, False authority, Red herring and Cherry picking), The argument schemes at play (including False analogy, Hasty generalisation, Post hoc and False cause), and Vagueness of the language.

A further source of guidance in relation to the recognition of Disinformation is government agencies whose role includes the integrity of elections. The Australian Electoral Commission provides commentaries on emotional language (particularly fearmongering), inconsistency in argument (which they refer to as 'incoherence'), false dilemmas (typically presenting two choices when more are possible), scapegoating (unjustifiably attributing a perceived problem to a particular person or group), attacks on individuals rather than arguments, disguised accusations (usually in the form of a question), and de-contextualisation such as quoting out of context (which they refer to as 'cherry-picking') (AEC 2022).

One potential source of insight, on examination, fails the need. Evidence-based medicine (EBM) appears not to have moved beyond its starting-point, which was randomized controlled clinical trials of very large-scale, that have been successfully replicated (REF). EBM is an entirely empirical approach, and constitutes a rejection of the time-honoured blend of theory and empiricism. Theory offers systemic explanations and is tested by and articulated, adjusted, and eventually replaced on the basis of evidence from the field (Sehon & Stanley 2003). To divorce theory from empirical data is to invite the error of mistaking correlation for causality. In any case, beyond medicine, the search for a coherent definition of, and process for, evidence-based practice appears to have stalled at the point of 'wise use of the best evidence available'.

In the broader area of 'misinformation in the digital environment', Ripoll & Matos (2019) propose a set of information reliability criteria. They first distinguish a 'technical dimension', which has its focus on the provenance of a work. Its elements are (pp.91-92):

Two of the authors' three 'steps' on the 'semantic dimension' are undermined by their weddedness to truth (veridicality and alethic modalities). Their third dimension, however, on pp.93-95, draws the distinction among Assertions of Fact (reflecting Popperian statement-refutability), Assertions embodying Values, variously "opinions, personal tastes, aesthetic criticism, ... interpretations of events [and judgments]" (p.94) and Conceptual Propositions. They warn of the risks of mixing the three categories, which is common in "the tactics of advertising and propaganda, marketing and image advisory [and] rhetorical, ideological and political discourses" (p.95).

No single work has been identified to date that provides authoritative and comprehensive analysis of reliability criteria for Textual Assertions, or guidance in relation to processes to authenticate the reliability of Textual Assertions. There is, however, a considerable body of theory on the subject, from which such guidance can be developed. Moreover, it is widely acknowledged that the development, articulation and application of such guidance is urgently needed, in order to counter the wave of Misinformation and Disinformation that has followed the collapse of the business model that funded 'responsible journalism', the democratisation of publishing, and the explosion in manipulative communications by marketers, political 'spin-doctors', 'moral minorities' and social media 'influencers'.

I contend that the Authentication of Assertions as to Facts lies within the domains of the IS discipline and IS practice. One reason for this is that both the uttering and the evaluation of Textual Assertions are dependent on information infrastructure, including IS that support the handling of text. Text has been supported by IS since the 1960s at least within free-form 'comments' data-items, but also by free-text search since c.1970 in the form of the Docu/Master, ICL Status and IBM STAIRS products (Furth 1974, Clarke 2013), and by library systems, initially for cataloguing and with a focus on metadata, but from the late 1970s for content.

There was an explosion in text-handling capabilities in the decades preceding the appearance of the World Wide Web and the widespread access to the Internet from the early 1990s onwards. Among the many threads of activity that the Web unleashed were easy self-publication of text-based pages, electronic publishing, electronic discovery of content, and web-crawlers and search-engines. Such services achieved maturity at the very beginning of the 21st century. Evidence management systems have emerged to support both law enforcement agencies and law firms engaged in civil litigation. Surveillance of text has become an important sub-field within the data/IT/cybersecurity field. These examples demonstrate that text has been increasingly absorbed into IS practice, and has attracted an increasing proportion of the time of IS researchers and the space in IS publishing venues.

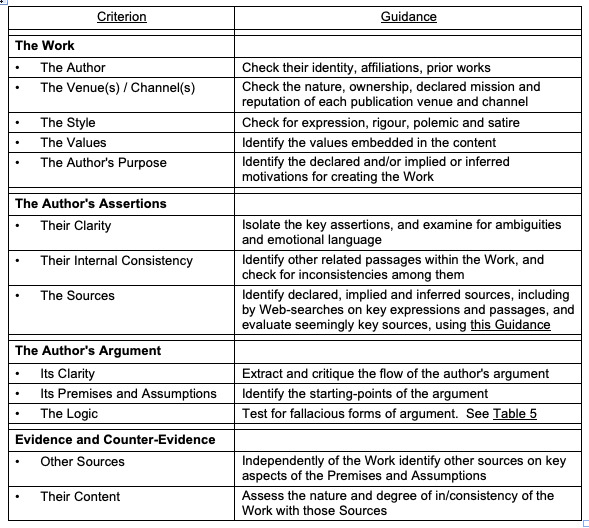

Moreover, emergent 'reliability criteria' to support the Authentication of Textual Assertions are capable of expression in terms familiar to IS practitioners, and that can be integrated into conventional IS processes. Table 6 provides a suggested set of criteria, and guidance as to their application.

[ In order to demonstrate the efficacy (or otherwise) of such guidance, it is intended that some test-cases of Textual Assertions as of Fact be devised, and the tentative criteria and guidance applied to them. For the very preliminary experiments, see Appendix 1. It is anticipated that these experiments will suggest that the emphasis on criteria needs to vary depending on the nature, content and context of the Assertions. It also appears likely that a fixed authentication process may be inadvisable. Instead, the time and effort needed to perform an assessment might be kept within bounds by prioritising consideration of those criteria that appear on first inspection to be least convincing, or most suspect, or most quickly tested. ]

This paper has applied a generic theory of Authentication to Assertions as to Fact. It has acknowledged the challenges involved, and the still-tentative state of knowledge in relation to criteria and process for distinguishing instances of Misinformation and Disinformation, and debunking them. It has argued that the IS profession and discipline need to be much more active in this field of endeavour. The Authentication of Assertions as to Fact is very important to economic, social, cultural and political discourse, and it is incumbent on IS practice and practice-oriented IS research to contribute to its conduct.

This has implications for IS practitioners. Most of their expertise-base has as its focus structured data. They therefore need to expand their horizons and competencies. This in turn has implications for education and training, which is the responsibility of employers as well as educational institutions, professional societies and providers of ongoing professional education. The call for greater contributions also has implications for practice-oriented IS research. Academics need to invest far more of their time into theory development relevant to, and empirical studies of, the handling and particularly the authentication of data in textual form.

Note: A couple of cases are being sought as exemplars of 'fake news', to check the usefulness of the Guidance in that context. Further cases follow that check the applicability of the Guidance in the rather different context of IS activities.

During 2003, the US Administration of George W. Bush enlists the UK Prime Minister Tony Blair to create public belief that Sadam Hussein's Iraq possessed 'weapons of mass destruction' (WMDs) and is prepared to use them, and hence invasion is justified.

No published information exists at the time to support the contention of the US and UK Governments. A recently-retired weapons inspector and a diplomat investigating reports about Iraq acquiring uranium disputes the claims. Shortly before the invasion, the UN inspection team led by Hans Blix declares it has found no evidence of the existence of WMDs. Following the invasion, no evidence emerges to substantiate either the claim that they existed, or that the US Administration reasonably believed it to be the case.

The absence of supporting sources, the thin veil of justification for refusing to provide that evidence, and the existence of sources supporting the contrary claim, were used to argue at the time that the US Administration was conducting a campaign of either Misinformation or Disinformation. The post-invasion absence of physical evidence and the cumulation of contrary testimony and counter-evidence subsequently made clear that was indeed the case. The US Administration appeared to opt for it to appear to have been a failure of intelligence ('misinformation') rather than a fabrication ('disinformation').

On 6 January 2021, Donald Trump addresses supporters at a rally 2.5 kilometers from the Capitol, where a joint session of Congress is conducting proceedings to certify the results of the election and thereby end Trump's Presidency. During the address, many hundreds of supporters stream towards the Capitol, and scores enter the premises. Several violent episodes occur. It takes 3 hours for order to be restored and the proceedings of Congress recommenced.

Shortly afterwards, Trump is the subject of an impeachment trial before the Senate. It is dismissed in February 2021. In early August 2023, Trump is indicted on several charges, one of which is that he "did knowingly combine, conspire, confederate, and agree with co-conspirators ... to corruptly obstruct and impede an official proceeding, that is, the certification of the electoral vote":

The facts of the proximity in space and time of Trump's address and the attack on the House do not appear to have been disputed. The Assertions as to Fact that are of importance are:

Original source-material is available in abundance, in video, audio and transcript forms. The issue is in the interpretation of Trump's spoken words, and for that independent sources need to be checked.

Incitement is a legal term. Under US law, to be incitement, speech has to be intended to cause violence, and has to be likely to cause imminent violent action. As a result, convictions are rare. Even in context, the key statements in Trump's lengthy address ('We will stop the steal', 'If you don't fight like hell you're not going to have a country anymore', 'We are going to the Capitol') appear unlikely to be found to represent incitement. The words, even in context, appear to encourage supporters to walk to the Capitol rather than to storm it, and hence neither (a) nor (b) appear tenable interpretations of the speech.

The terms of the August 2023 indictment, on the other hand, are subject to quite different tests, have at least prima facie credibility, and will be considered by a court not a Party-riven chamber of the Congress.

The intention in contriving these examples is to check the applicability and usefulness of the guidance in Table 6 in IS contexts. All cases so far are very preliminary / unsatisfactory / a-bit-beside-the-point.

Note: This case is loosely based on actions by a CEO of an Australian Emergency Services agency in the years either side of the year 1990:

A not-for-profit engages and trains volunteer emergency responders across a wide geographical area. It has been successfully pursuing a growth strategy. It has steadily increased its resources and capabilities, and established a record of responding effectively and quickly to demands for its services. Leveraging off that reputation, it has acquired bank loans to fund equipment purchases, and attracted a steady flow of new volunteers. Because the agency has many sites, the governing board is familiar with only the agency's main offices and nearby depots. However, it receives informative written reports from the CEO on a quarterly basis, and a formal annual report including both financial and statistical data and an audit report.

It is conventional for a governing board to work closely with the CEO, and to depend on reports provided by the CEO. Of the few independent sources of information that are readily available, most are media reports on the agency's actions in relation to particular, often dramatic events. The run of success under the CEO has been so significant that the expense of occasional external reviews of aspects of the organisation's operations has not been seen to be warranted.

In evaluating the CEO's claims relating to the operation, there are few opportunities to apply the primary Criterion of 'Other Sources of Evidence and Counter-Evidence'. The annual audit report accordingly has even more significance than usual. However, all audit reports are long, cautiously worded, and mostly boilerplate that appears in every report to every organisation. Moreover, the primary function of much of the text is to minimise the auditor's risk of being sued by their client. Despite this, an alert board-member notices that a page of the current year's audit report is missing from the copy sent to them. When a copy of the missing page is eventually acquired, it is found to contain a repetition of previous qualifications to the audit, relating to the inability of the auditor to confirm the existence of a significant proportion of the organisation's claimed safety equipment asset-base, which is used as surety against the bank-loans.

Note: This case is loosely based on the Australian Robodebt initiative of 2015-20:

The Australian social welfare payment each fortnight depends on the amount of income the individual has declared for the previous fortnight. Because the large majority of recipients are in, at best, sporadic employment, a proportion of payments are made in excess of the schedule. As part of the process of recovering overpayments, the social welfare agency intends to acquire the data declared annually to the taxation agency, divide it by 26 to impute fortnightly earnings, and demand repayment of amounts that have been paid in excess of that which appears from that data to have been due.

During the plan's conception and articulation, a report by the agency's in-house counsel questions its likely effectiveness and advises that it is unlawful. Senior executives suppress the report, ensuring it does not come to the Minister's attention. They draft the Cabinet Minute approving the scheme in such a manner that Cabinet assumes legality has been established.

After implementation, some frontline staff express serious concerns, but senior executives ignore them, weaponise the agency's Code of Conduct and threaten repercussions if information leaks beyond the agency, sack a contractor with immediate effect who declines to approve release of software without the completion of testing, exercise control over the content of one consultancy report, suppress another consultancy report, and avoid commissioning further consultancy reports.

Executives also ignore the many media articles on the scheme, and cow agency clients by illegally releasing the personal information of complainants. With the assistance of in-house legal counsel, executives contrive to avoid negative actions by three agencies with oversight responsibilities, ignore a series of unpublished tribunal decisions that question the scheme's legality, ignore a widely-reported article by a retired and well-reputed tribunal member, and utilise various strategems to avoid cases reaching the court. Ministers parrot speaking notes that sustain the public lie that the mechanism is lawful. Eventually, a case makes its way into a senior court, and the judgment brings down the house of cards.

An active disinformation campaign triumphed for 5 years, because committed, skilful behaviour by senior executives, in breach of logic, policy and the law, prevented clear evidence of illegality becoming publicly apparent, thereby holding at bay the ability of opponents to apply the Reliability Criteria and expose the fraud.

The need is for a couple of vignettes that are recognisably within-scope of IS practice and research, push beyond structured data into text, but appear to be tractable.

Case B1 is about Assertions as to Facts about the existence of claimed assets. This could be complemented by a tale about Assertions about the value of assets as a particular time (adopting an accounting and compliance perspective).

Alternatively, the vignette could involve Assertions about the potential future value of assets (the investment perspective). One context is the evaluation of business cases brought forward within an organisation. Another is investments, whether by corporations, individuals or superannuation funds, e.g. in 'tech stocks' particularly those making next-great-thing claims (recent-past blockchain, currently AI, next-round maybe quantum-tech). Another field of dreams is relatively scarce raw materials needed by suppliers of renewable energy products. The focus has mostly been on materials for batteries, in particular lithium, graphite, cobalt (or nickel and manganese) and rare earths, and maybe even copper.

A more prosaic idea is Assertions by job-applicants about their qualifications. Similar patterns arise in relation to consultancy firms' capabilities statements and claims relating to assignments previously performed.

Another possible area is the evaluation of Assertions in insurance claims, involving checks of internal consistency, checks against any physical and documentary evidence, any supplementary vocal responses to enquiries, and independent sources.

AEC (2022) 'Disinformation Tactics' Australian Electoral Commission, 2022, at https://www.aec.gov.au/media/disinformation-tactics.htm

ALRC (2010) 'Uniform Evidence Law' Australian Law Reform Commission, Report 102, August 2010, at https://www.alrc.gov.au/publication/uniform-evidence-law-alrc-report-102/12-the-credibility-rule-and-its-exceptions/the-definition-of-substantial-probative-value/

Altinkemer K. & Wang T. (2011) 'Cost and benefit analysis of authentication systems' Decision Support Systems 51 (2011) 394-404

Clarke R. (2013) 'Morning Dew on the Web in Australia: 1992-95' Journal of Information Technology 28,2 (June 2013) 93-110, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/II/OzWH.html

Clarke R. (2016) 'Big Data, Big Risks' Information Systems Journal 26, 1 (January 2016) 77-90, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/BDBR.html

Clarke R. (2021) 'A Platform for a Pragmatic Metatheoretic Model for Information Systems Practice and Research' Proc. Austral. Conf. Infor. Syst. (ACIS), December 2021, PrePrint at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/PMM.html

Clarke R. (2023a) 'A Generic Theory of Authentication to Support IS Practice and Research' Working Paper, Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, March 2023, at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/PGTA.html

Clarke R. (2023b) 'The Theory of Identity Management Extended to the Authentication of Identity Assertions' Proc. 36th Bled eConf., June 2023, at http://rogerclarke.com/ID/IEA-Bled.html

Derrida J. (1967) 'Of Grammatology' Johns Hopkins Univ Press, 1967

DIGI (2021) 'Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation' Digital Industry Group Inc., October 2021, at https://digi.org.au/disinformation-code/

EU (2022) 'The Strengthened Code of Practice on Disinformation' European Commission, June 2022, at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/2022-strengthened-code-practice-disinformation

Floridi L. (2007) 'In defence of the veridical nature of semantic information' European Journal of Analytic Philosophy 3,1 (2007) 31-41, at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353346766_In_Defence_of_the_Veridical_Nature_of_Semantic_Information

Floridi L. (2011) 'The philosophy of information' Oxford University Press, 2011

Furth S.E. (1972) 'STAIRS - A user-oriented ful text retrieval system' Law and Computer Technology 5, 5 (Sep-Oct-1972) 114-119

Gadamer H.G. (1976) 'Philosophical Hermeneutics' Uni. of California Press, 1976

Hamblin C.L. (1970) 'Fallacies' Methuen, 1970

Heidegger M. (1962) 'Being and Time' Harper & Row, 1962, at http://users.clas.ufl.edu/burt/spliceoflife/BeingandTime.pdf

IFLA (2017) 'How to Spot Fake News' Infographic, International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, March 2017, at https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/167

Morris C. (1938) 'Foundations of the theory of signs' University of Chicago Press, 1938

Musi E. & Reed C. (2022) 'From fallacies to semi-fake news: Improving the identification of misinformation triggers across digital media' Discourse & Society 2022, Vol. 33(3) 349-370, at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/09579265221076609

Nickerson R.S. (1998) 'Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises' Review of General Psychology 2, 2 (1998), at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

OL (2016) 'Word of the Year 2016' Oxford Languages, 1 November 2016, at https://languages.oup.com/word-of-the-year/2016/

Ramoo D. (2021) 'Writing Systems', Chapter 7 of 'Psychology of Language' BCcampus, 2021, at https://opentextbc.ca/psyclanguage/

Ripoll L. & Matos J.C. (2019) 'Information reliability: criteria to identify misinformation in the digital environment' Investigacion Bibliotecologica 34,84 (julio/septiembre 2020), pp. 79-101, at https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S0187-358X2020000300079&script=sci_arttext

Salop S.C. (2017) 'An Enquiry Meet for the Case: Decision Theory, Presumptions, and Evidentiary Burdens in Formulating Antitrust Legal Standards' Georgetown University Law Center, 2017, at https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3025&context=facpub

Sample I. (2020) 'What are deepfakes - and how can you spot them?' The Guardian, 13 Jan 2020, at https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/jan/13/what-are-deepfakes-and-how-can-you-spot-them

Searle J.R. (1975) 'A Taxonomy of Illocutionary Acts' in Guenderson K. (ed.) 'Language, Mind, and Knowledge' Uni. of Minnesota, 1975, pp.344-369, at https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/185220/708_Searle.pdf?sequence=1

Sehon S.R. & Stanley D.E. (2003) 'A philosophical analysis of the evidence-based medicine debate' BMC Health Serv Res 3,14 (2003), at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC169187/

Soe A.O. (2019) 'A Floridian dilemma: Semantic information and truth' Information Research 24,2 (June 2019), at https://informationr.net/ir/24-2/paper827.html

Sukhodolov A.P. & Bychkova A.M. (2017) 'Fake news as a modern media phenomenon: Definition, types, role of fake news and ways of taking measures against it' Voprosy teorii i praktiki zhurnalistiki / Theoretical and Practical Issues of Journalism 6,2 (2017) 143-169, at https://doi.org/10.17150/2308-6203.2017.6(2).143-169

Tindale C.W. (2007) 'Fallacies and Argument Appraisal' Cambridge University Press, 2007

Tiruneh D.T., Verburgh A. & Elen J. (2014) 'Effectiveness of critical thinking instruction in higher education: a systematic review of intervention studies' High. Educ. Stud. 4, 1 (2014) 1-17

Unicode (2022) 'Universal Coded Character Set' UCS, ISO/IEC 10646, v.15.0, September 2022, at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode15.0.0/

Wardle C. (2017) 'Fake news. It's complicated' First Draft, 16 February 2017, at https://firstdraftnews.org/articles/fake-news-complicated/

Winograd T. & Flores F. (1986) 'Understanding Computers and Cognition' Ablex, 1986

Woods J., Irvine A. & Walton D. (2004) 'Argument: Critical Thinking, Logic and the Fallacies' Prentice Hall, 2nd Edition, 2004

Yu H. & Wu C. (2016) 'Recreating the image of Chan master Huineng: the roles of Mood and Modality' Functional Linguistics 3, 4 (February 2016), at https://functionallinguistics.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40554-016-0027-z

Roger Clarke is Principal of Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, Canberra. He is also a Visiting Professor associated with the Allens Hub for Technology, Law and Innovation in UNSW Law, and a Visiting Professor in the Research School of Computer Science at the Australian National University.

| Personalia |

Photographs Presentations Videos |

Access Statistics |

|

The content and infrastructure for these community service pages are provided by Roger Clarke through his consultancy company, Xamax. From the site's beginnings in August 1994 until February 2009, the infrastructure was provided by the Australian National University. During that time, the site accumulated close to 30 million hits. It passed 65 million in early 2021. Sponsored by the Gallery, Bunhybee Grasslands, the extended Clarke Family, Knights of the Spatchcock and their drummer |

Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd ACN: 002 360 456 78 Sidaway St, Chapman ACT 2611 AUSTRALIA Tel: +61 2 6288 6916 |

Created: 27 June 2023 - Last Amended: 8 August 2023 by Roger Clarke - Site Last Verified: 15 February 2009

This document is at www.rogerclarke.com/ID/ATS.html

Mail to Webmaster - © Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2022 - Privacy Policy